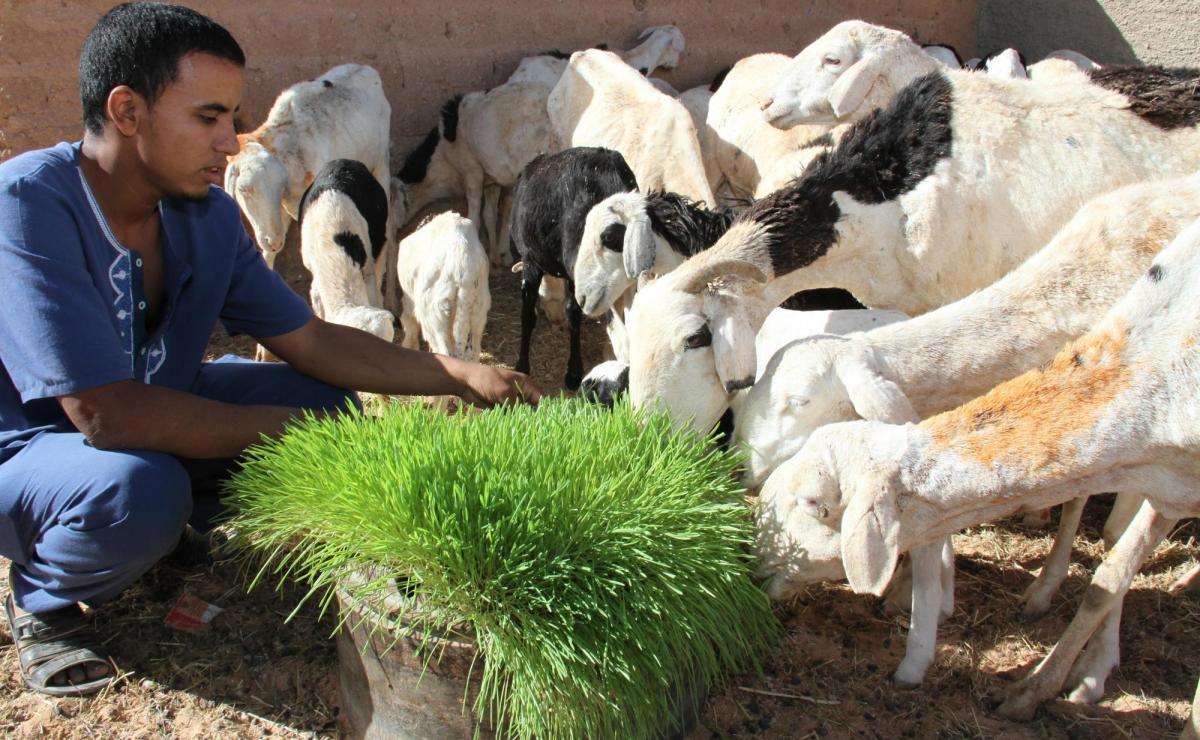

H2Grow is using low-tech hydroponic units to help Sahrawi refugees grow fresh green animal fodder locally and strengthen food security in the community.

Hydroponics is a soilless cultivation technique that enables plant growth in areas that are non-fertile, arid or urban with limited space. It is a cost- and time-efficient method, requiring about 90% less water than traditional agriculture. The semi-nomadic Sahrawi refugees greatly value livestock for milk and meat. However, due to the Algerian desert’s arid climate, agriculture is extremely poor and goats in the camps often end up eating garbage.

Thus, WFP and local experts developed a low-tech system to grow barley for use as animal fodder by refugees in camps in Tindouf, south-western Algeria. The fodder increases the refugees’ access to milk and meat, thereby improving food security in the camps. Hydroponics is particularly suited to harsh environments, such as those in which many of the world’s refugee camps are located. The low-cost model can easily be scaled and replicated in other vulnerable communities.

In 2017, the team tested different hydroponics solutions with refugees through various iterations, moving from an initial high-tech solar-powered container to the design and implementation of small, DIY household units built with locally procured materials and at 10% of the cost. As a result, training and sensitization campaigns were conducted alongside of the installation of 50 large units as well as smaller household kits to grow barley.